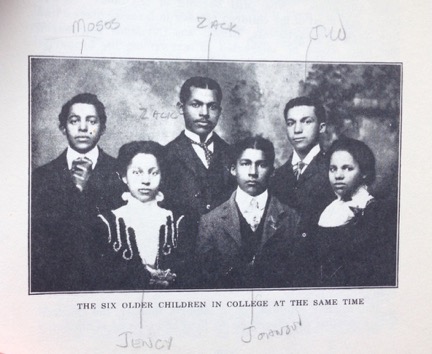

Zach Hubert came out of slavery with an adage that he would pass on to his children, and his children’s children, and their children down the line. “Get your education,” he would always say to them when his family gathered together in later years. “It’s the one thing they can’t take away from you.”

Zach grew up a slave on the Hubert plantation in Georgia’s Warren County. Most slaves on the plantation were forbidden to have books, but Zach was the same age as the plantation owner’s son, and the boy taught Zach how to read.

When freedom came to Georgia, Zach and his wife rented a farm and worked until they saved enough money to buy some land. They had 12 children, seven boys and five girls, and Zach set up a school and hired a teacher to educate them.

When they came of age, those children did something that would have been unthinkable for Zach and his peers.

They went to college.

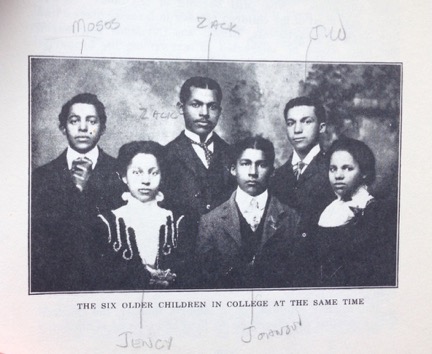

Students on the campus of Howard, 1870.

Prior to the Civil War, there was no structured higher education system for Black students. Public policy and certain statutory provisions prohibited the education of Black students in various parts of the nation. The Institute for Colored Youth, the first higher education institution for Black students, was founded in Cheyney, Pennsylvania by a group of Philadelphia Quakers in 1837. It was followed by two other Black institutions--Lincoln University, in Pennsylvania (1854), and Wilberforce University, in Ohio (1856). A college education was also available to a limited number of students at schools like Oberlin College in Ohio and Berea College in Kentucky.

Many more such schools were founded during Reconstruction:

1865: Bowie State University is founded as Baltimore Normal School. Clark Atlanta University is established by the United Methodist Church. Originally two separate schools—Clark College and Atlanta University—the schools merged. The National Baptist Convention opens Shaw University in Raleigh, NC.

1866: The Brown Theological Institute is opened in Jacksonville, Fl. By the AME Church. Today, the school is known as Edward Waters College. Fisk University is founded in Nashville, Tenn. The Fisk Jubilee Singers will soon begin touring to raise money for the institution.

Lincoln Institute is established in Jefferson City, Mo. Today, it is known as Lincoln University of Missouri.

Rust College in Holly Springs, Miss. opens. It is known as Shaw University until 1882. One of Rust College’s most famous alumna is Ida B. Wells.

1867: Alabama State University opens as Lincoln Normal School of Marion. Barber-Scotia College opens in Concord, NC. Founded by the Presbyterian Church, Barber-Scotia College was once two schools—Scotia Seminary and Barber Memorial College. Fayetteville State University is founded as Howard School. The Howard Normal and Theological School for the Education of Teachers and Preachers opens its doors. Today, it is known as Howard University. Johnson C. Smith University is established as the Biddle Memorial Institute. The American Baptist Home Mission Society founds the Augusta Institute, which is later renamed Morehouse College. Morgan State University is founded as Centenary Biblical Institute. The Episcopal Church provides funding for the establishment of St. Augustine’s University. The United Church of Christ opens Talladega College. Known as Swayne School until 1869, it is Alabama’s oldest private Black liberal arts college.

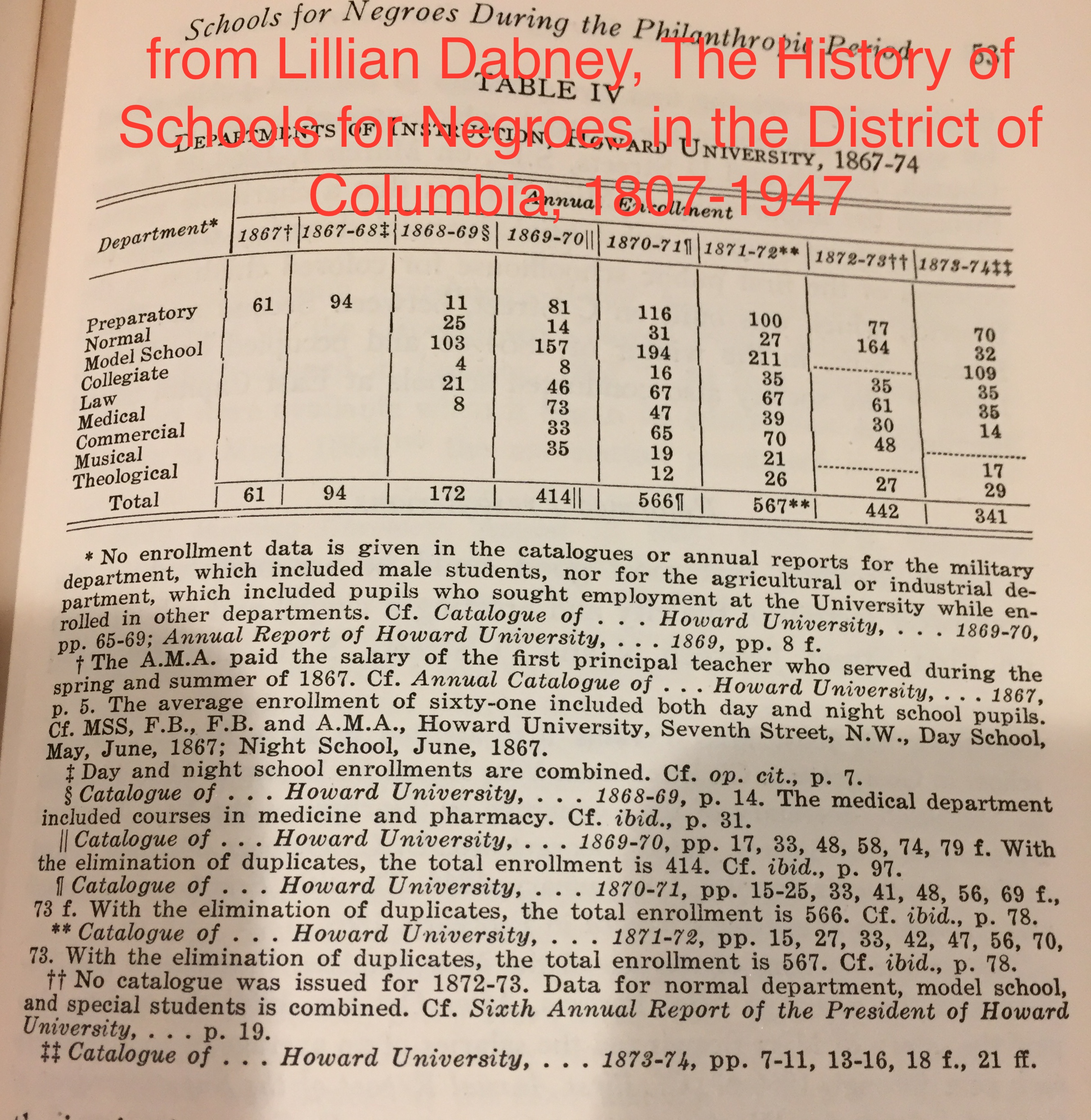

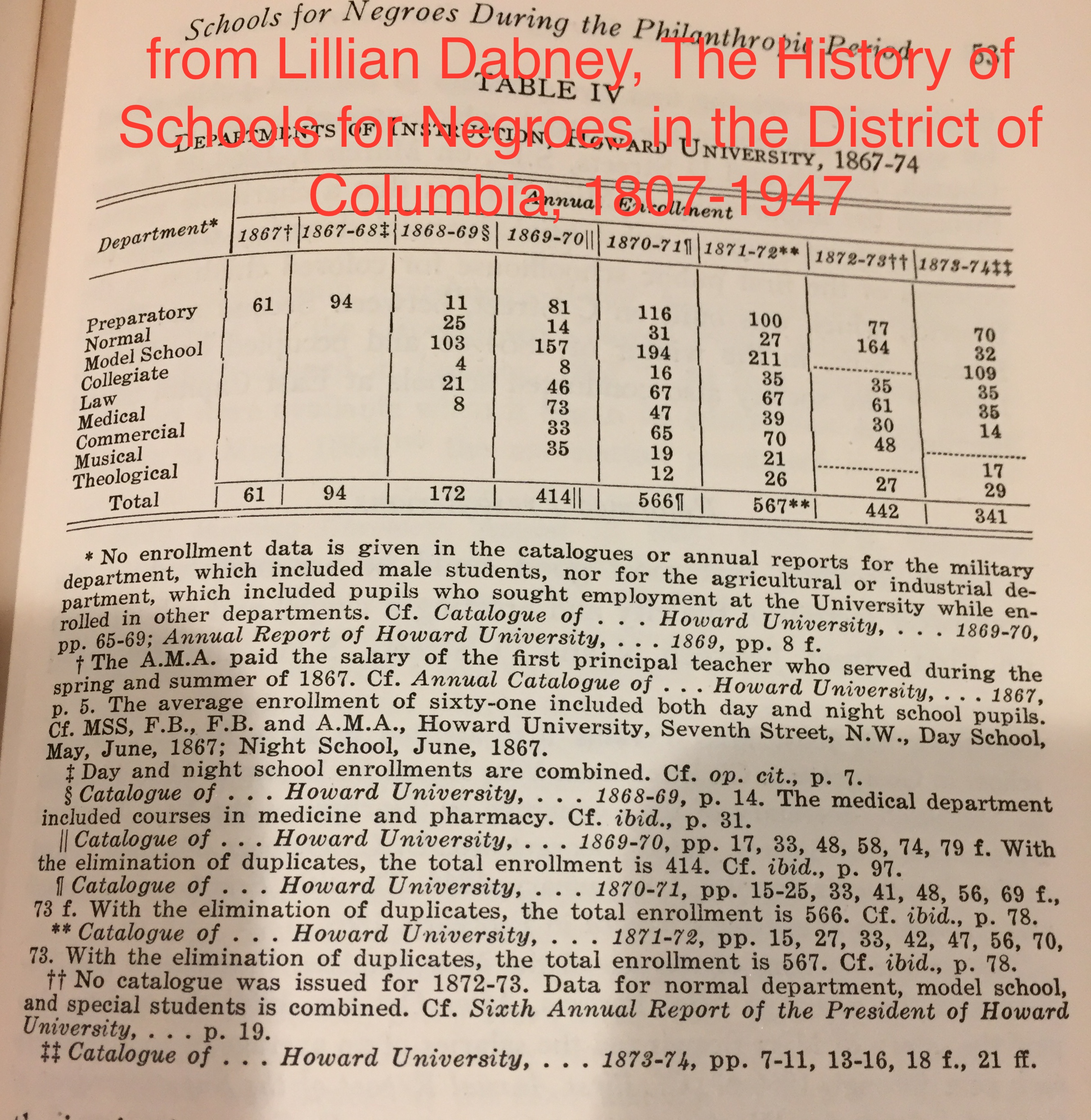

I nerded out and did a quick research project on Howard. Andrew Johnson, a notorious racist, signed the Howard charter on the same day (3/2/67) Congress overrode his veto of first Reconstruction Act. Historian Rayford Logan, from Howard University: The First Hundred Years, 1867-1967: “A plausible guess is Johnson signed so many bills on March 2 that he did not know the purpose and scope of Howard’s Charter.” The school opened May 1867.

Howard was planned as an integrated school by both sex and race, but one by-law stated that “Every person elected to any official position…shall be a member of some Evangelical Church.”

The first 3-5 students (it’s not entirely clear; see p. 34) were white women, the daughters of 2 members of the Board of Trustees; it had a Normal Department, intended to teach teachers, and a Preparatory Department, which prepped students for college. The 3-year Preparatory curriculum included 3 years of Latin, 2 of Greek, one of arithmetic, and one of algebra. There was one teacher from May to July. Student body reaches 64 in August, ages 13-30. Enrollment 57, 1869; 108, 1874.

The collegiate department opened 1868 with 2 professors and one student, 4-year, largely classical curriculum. (For a sense of what that taught, here’s the Harvard entrance exam, 1869.)

Graduates:

Normal Dept.: 7, 1870; 9, 1871; 10, 1872; 0, 1873; 7, 1874 (of these 33, 27 were female)

Preparatory Dept.: 29, 1872; 18, 1873; 7, 1874 (of these 54, 3 were women). Inman Page, class of 1872, was one of the first two African-American students at Brown. He was named class orator as a senior and delivered a speech called “The Intellectual Prospects of America.” (I read some of it and found it slow going. Page does not, at least in what I read, discuss race at all.) Wiley Lane, ’73, graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Amherst in 1879.

Collegiate dept graduated 2, 1872; Howard

also had a medical school (opened 1868), law school (1869)—10 graduates, 1871; theological dept (1870); also agricultural, industrial, commercial, military, music depts, with varying success.

1868: Hampton University is founded as Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute. One of Hampton’s most famous graduates, Booker T. Washington, later helped to expand the school before establishing Tuskegee Institute.

1869: Claflin University is founded in Orangeburg, SC. The United Church of Christ and United Methodist Church provide funding for Straight University and Union Normal School. These two institutions will merge to become Dillard University. The American Missionary Association establishes Tougaloo College.

1870: Allen University is founded by the AME Church. Established as Payne Institute, the school’s mission was to train ministers and teachers. The institution was renamed Allen University after Richard Allen, founder of the AME Church. Benedict College is established by the American Baptist Churches USA as Benedict Institute.

1881: Atlanta Female Baptist Seminary is founded by two educators from Massachusetts, Sophia B. Packard and Harriet Giles, both members of the same Baptist Home Mission Society that founded Morehouse. Its name is changed to Spelman Seminary in 1884 to honor Laura Spelman Rockefeller, daughter-in-law of tycoon John D. Rockefeller, who donated to the school in 1882. (Her parents are described as "fearless and powerful abolitionists" whose house was a stop on the Underground Railroad in Candacy Taylor's Overground Railroad.) The first graduating class receives high-school diplomas in 1887, and Spelman becomes a college in 1897. (Its charter from Georgia in 1888 describes it as "an Institution of learning for young colored women, in which special attention is to be given to the formation of industrial habits and of Christian character.") As Alexandra observed, this is alluded to in the school hymn:

We'll ever faithful be

Throughout eternity.

May peace with thee abide

And God forever guide

Thy heights supreme and true.

The first two graduates carry on legacies: Jane Anna Granderson is the granddaughter of Lilly Ann Granderson, who ran a secret school to teach literacy under slavery. There's a children's book about her. Jane Anna Granderson subsequently taught at Spelman, and her "personality and public addresses in New England won so many friends to the education of colored women," wrote Missions, a Baptist magazine, in 1911. Claudia T. White was the daughter of William Jefferson White, founder of Morehouse. (Here's a piece she wrote defending women's education in 1897.) She taught German and Latin at Spelman before marrying a professor from the men's college and retiring. In a letter to the same Baptist magazine in 1912, she noted that 9 of the first 14 female graduates had gone into teaching: "all these, of whom I am glad to count myself one, are trying to pass on to others that which they have received, with increment, and to bear their share of the responsibility that rests upon those who have enjoyed great opportunities." Her daughter also attended Spelman.

Although these institutions were called universities" or "institutes" from their founding, a major part of their mission in the early years was to provide elementary and secondary schooling for students who had no previous education. “They started in church basements, they started in old schoolhouses, they started in people’s homes,” says Marybeth Gasman, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania who studies HBCUs. “[Former slaves] were hungry for learning…because of course, education had been kept from them.” Their leadership was mostly white—not until 1926 did Howard have its first African-American president, Rev. Mordecai Johnson. Fisk did not until 1946, with Dr. Charles Spurgeon Johnson. Hampton did not until 1949, with Dr. Alonzo Moron. It was not until the early 1900s that HBCUs began to offer courses and programs at the postsecondary level.

Following the Civil War, public support for higher education for Black students was reflected in the enactment of the Second Morrill Act in 1890. The Act required states with racially segregated public higher education systems to provide a land-grant institution for Black students whenever a land-grant institution was established (14 of the 17 Southern states that ordered segregated education refused to provide land-grant colleges until Congress forced them to do so) and restricted to white students. As a result, some new public Black institutions were founded, and a number of formerly private Black schools came under public control; eventually 16 Black institutions were designated as land-grant colleges. These institutions offered courses in agricultural, mechanical, and industrial subjects, but few offered college-level courses and degrees.

Sources:

"About Us," Spelman College

Samara Freemark, “The History of HBCUs in America,” American RadioWorks (Aug. 20, 2015),http://www.americanradioworks.org/segments/hbcu-history/

Lynn D. Gordon, "Race, Class, and the Bonds of Womanhood at Spelman Seminary," History of Higher Education Annual (1989)

“HBCU Timeline: 1837 to 1870,” http://afroamhistory.about.com/od/timelines/fl/HBCU-Timeline-1837-to-1870.htm

“HBCUs in America: A Short History,” African American Registry, http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/hbcus-america-short-history

“Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Higher Education Desegregation,” US Department of Education, ”https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/hq9511.html

“The History of Historically Black Colleges and Universities: a tradition rich in history,” CollegeView, http://www.collegeview.com/articles/article/the-history-of-historically-black-colleges-and-universities